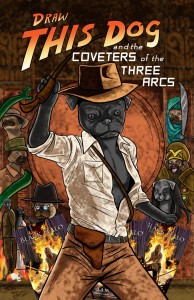

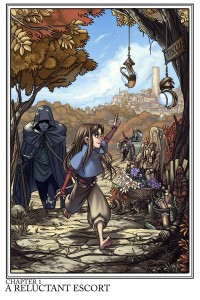

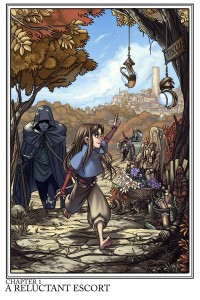

Did you read Ashley Cope’s Unsounded, like I asked you to?

If you did, you’ll have doubtlessly found what I did when the goons brought it to my attention: a magical world wrought with wonder and mysticism that builds without overbearing, an incredibly deep relationship between two misfits that both repulses and attracts, an undercurrent of danger and depravity that courses through the entire story, expertly paced.

If you didn’t, then I hate you.

But, I digress…

Unsounded follows the adventures of Sette, a feral, foul-mouthed child thief, as she is escorted through the land by her unwilling companion, the Galit Duane: spellwright, good Aldishman, zombie. It’s also a comic I marvel at for its ability to get just about everything right. A light read-through will reveal Ashley Cope’s distinct talent for fantasy writing: likable characters, magic that is actually wondrous and societies as bizarre as the creatures that live in the wildernesses alongside them. But a deeper look will reveal that this comic has an amazing grasp on craft: pacing, worldbuilding, exposition and character relationships are handled with much more finesse than you would expect from your average comic.

Ms. Cope agreed, at my whining plea, to talk about this craft with me. I hope you enjoy what I had to ask and what she had to say.

So, it’s essentially mandated that any fantasy debate at least include the topics of world building and magic systems. I’ve often thought of them as largely hazardous concepts when people focus exclusively on them and neglect aspects like character and conflict, but one of the things I really enjoy about Unsounded is that the magic and the world’s details are expertly paced. We get a glimpse into a magical world filled with wonder and its societies as they pertain to the story.

How much of that is deliberate and how much of it is whimsy? By that, I mean, are these societies and details mapped out and deliberately seeded throughout the story? Or is it sort of a case of “wouldn’t it be cool if we had a giant walking tree monster…how can I put that in?” What do you prefer working with?

Balancing world information with narrative is one of the most difficult things about working in fantasy, and I’ll hurl that challenge at any author who scoffs at the genre. It’s particularly difficult in comics. A fantasy novel can dump paragraph upon paragraph of setting information, and detail even complex systems pretty thoroughly right off. A comic is limited, essentially, to character dialogue; character dialog that eats up precious page space and which has to be used with great discerning and economy.

For that reason, all of the setting details and where they are revealed in Unsounded are very deliberately mapped out. I could fill up a wiki with the amount of information I’ve developed for the comic’s world but I’ve tried very hard to keep unimportant details off the page so far. Editing out irrelevant details is what I actually have the most problems with. Some details, however, serve a character-building or thematic role on occasion. The wandering root was not only a fun and unexpected monster – its empathic nature allowed it to serve as a visual manifestation of Duane and Sette’s relationship. Perhaps it’s foreboding that Duane had to violently put it down. The shrines and statues of gods seen on occasion are often pictured where the actual interference of gods to protect innocents would be expected – but that interference doesn’t come. The giant dogs represent the defeat of leisure and fealty by the capitalist demands of poorly compensated labour– haha, no, that’s a lie. Who doesn’t like giant dogs?

Speaking of pacing, we should probably address just how well Unsounded accomplishes this. It has a real flair for blending the details of the world in with the characters’ own stories and keeping up the suspense. Nothing really feels like you’re doing things just to do them.

I suppose it relates back to the question of planning versus growing, save that it’s a question of how much do you reveal about each character and the world and in what order? Are there some characters that require a lot of fleshing out and exposition? Or are you comfortable leaving the reader to make their own assumptions?

Thank you! Pacing is really difficult for anyone but in webcomics, I believe how you post the pages can be just as important as what’s on the pages. If you have five pages that flow together and depict one important action or one slowly shifting tone or mood, you MUST post those pages together. Be a professional, care about your story, plan ahead, and get those pages done so that you can post them in a way that benefits your pacing. So many great scenes in so many webcomics have been diminished because of a poorly thought-out posting schedule. Dramatic webcomics must overcome this strict one-page-at-a-time hurdle and the even worse post-when-you-feel-like-it hurdle.

That mini-rant aside, I believe that fleshing out a character can be done with real brevity if you do plan and trust your readers to squint between the lines. Sette, for instance, is intolerable. I don’t expect anyone to like her much, but I’ve painted the whole of her background already for anyone who cares to look. I didn’t do this by giving her a tear-ridden soliloquy – just explained the rough logistics of her background, who her dad is, and showed a few flashes of what life may be like for her back home. Her personality itself and how she treats people hopefully hammers home what’s always been expected of her and how she’s been raised. She’s not an obnoxious imp because I think that’s cute and endearing. In giving her so much page time I have to ask for a lot of trust from the reader. She’s been a risky character from page one.

Epic fantasy is always difficult to pace. Most authors seem to find the solution in starting off small. Everyone knows the Hero’s Journey model. It’s a little played out though, isn’t it? Maybe the protagonists shouldn’t be heroes. Maybe the story should start with the characters already in the middle of a journey. I won’t always succeed with what I do but I hope I always at least crash and burn in interesting ways.

Another tremendous aspect of Unsounded are the changes of tone that so well serve to reveal aspects of the world and characters that aren’t apparent or wouldn’t be talked about in natural conversation (Duane’s communion with the summoned beast comes to mind). The changes in tone really bring about another mood to the scenes before us, ramping up tension and turning it into horror.

A lot of this is accomplished by the sudden changes in artistic style, of course, but what do you do in terms of writing? In the previous example, we go further into Duane’s head than we ever have. Is it all an opportunity to delve further into the characters’ minds? Do you have any questions you ask yourself or techniques you practice to reach the mood you want to?

Generally when it comes to mood I try to keep my themes in mind, and I try to always interpret the visuals and the narrative through the lens of the currently pertinent character. For instance, most of the first chapter is a manic, cartoony and exaggerated romp. It’s Sette’s chapter. It only turns more morose when Duane’s rattled by what he finds inside the tree monster, and later when Sette’s hurt. Chapter 2, after the gloomy opening scene, is still under Sette’s thrall up until the scene you mentioned, when Duane is struck by his own similarity to the summoned beast and forcefully commandeers the mood and the narrative for a few pages. I let the art and his dialog reflect this. Again it asks for trust from the reader because it’s a shift towards the angsty, and pretty different from what they’ve been seeing, but I believe if you’ve made the reader care about the characters – not necessarily relate to them but care about them – you can get away with a shift like this.

It’s safe to say, being a fan of the comic, I’m a fan of Sette and Duane’s relationship. Beyond just the clever banter and genuine moments of affection between them, though, the relationship becomes a character unto itself: an antagonist, really.

I know from experience it’s a lot to ask of readers to like two characters who don’t like each other (and possibly themselves). But what do you do? Ever have any moments where you look at an exchange between them and cringe, thinking “well, that’s too much?” Is it an excuse to push the reader a little?

Oh, you have no idea. The pages I’m producing right now are about eighty pages beyond what’s been posted, and I’m still battling the monster that is Sette and Duane’s relationship. It’s obviously not a monster that’s going to be decapitated on one page – readers hate easy victories – but how much of Sette’s abuse and Duane’s stubbornness can the narrative tolerate? It’s not easy and I’m editing dialog right down to the minute a page goes live.

I think there’s naturally an expectation that they’ll reconcile their differences – that Sette will either grow up or Duane will drop his posturing and sink more to her level. A reconciliation has to happen but how it does so and what happens to complicate it are hopefully driving mysteries of the story.

Beyond Sette and Duane’s relationship, the strip’s central antagonist so far seems to be the Red Berry Boys, whose plot we’re still not sure of beyond its absolute horror. I can attest that there’s an immensely unnerving scene involving a small girl.

The topic of what’s necessary and what’s edgy for the sake of edginess comes up a lot in fiction, particularly fantasy. People occasionally wonder and constantly argue over whether traumatic acts like rape or murder serve a purpose beyond attempting to shock the reader. Where do you stand on this? Under what circumstances is it okay to cross that line? Or is the fact that it’s not okay the entire reason to do it? To shock? Or to talk about the issue? Or to establish character?

When that “immensely unnerving scene” was first posted it received a mix of reactions. Some readers did think it was exploitative but I don’t roll that way. What I was trying to do was a chiaroscuro contrast of tones between two girls. Sette’s extreme and manic, almost cartoonish personality contrasted with Cara’s bleak, brief, bloody scenes. That contrast was, to me, what really made that “unnerving scene” so jarring. From the first page of the comic I was setting up a tonal expectation in the reader and anticipating shattering it.

I think all the reasons you suggested are valid reasons to go explicit though. An author shouldn’t ignore any tool in their toolbox, no matter how unsavoury. Not every author is very skilled at using those tools though. I know there are a lot of comic book readers (including me) sick of writers playing the rape card. That doesn’t make rape an inviable character motivation but it does seem to mean there are a lot of writers out there who really suck at dealing with it.

I often find myself at a crossroads when it comes to magic. I despise the concept of “magic systems” being the crux of a story and I also loathe the wave-away answer of “magic is magic.” I’m pleased that Unsounded has avoided both of these by creating something with clear rules and ritual, but also by having just enough unexplained that it’s still wondrous.

Which do you lean more toward? Magic being something inexplicable or magic being something hard and fast? How much do you think you could push a reader in one direction or the other?

I’m a huge Doctor Strange/classic Marvel magic fan. That means I don’t have too much of a problem with loose magic rules. One of the reasons fantasy is so enduring is the presence of magic and the supernatural – keen stuff we don’t have in the real world. I think I can’t get too into scifi because it often wants the magician to explain the magic tricks. I don’t need to see the man behind the curtain.

But! That’s just personal preference. I realise vague magic is a dangerous thing in a story and Unsounded actually has a very detailed system with its own rules and internal logic. Of course it hasn’t been explained yet because it’s not important yet, but it’s a departure from element-based systems. There is a magic battle in Chapter 5 wherein some of the mysteries of the arts are cleared up. Still, there are certain Big Questions I don’t believe it’s ever right to answer in a story. It is presumptuous and preachy.

Finally, what influences you? It’s safe to say that Unsounded is pretty marvelously unique, but what’s inspired you? Or are there any comics, literature or other media that you just like?

I love Herman Melville. I’m one of those fans who can tell you his childrens’ names and the date of his death and the name of the whaling ship he worked on. His novels have always driven me.

I like an eclectic mix of comics. Though Miyazaki, Range Murata, and Mahiro Maeda are some of my favourite artists ever, I’m less enthusiastic towards manga than a lot of webcomickers out there. I like Alan Moore because he’s a reminder that symbolism and the metaphysical are okay in comics that also have punching and tentacles. Jeff Smith and Ross Campbell are amazing draftsman. Sam Kieth’s imagination is deadly. Gurihiru Studios does some mighty fine work

I find video games (Vagrant Story, Bioshock, and the Legacy of Kain series are favourites) and classic horror films are great ways to unwind. There is nothing in my life more detrimental to Unsounded’s page buffer than addictive video games. Arkham Asylum was eating chapter 4 for a while!

And that’s it!

I hope you enjoyed the shit out of this interview and continue to enjoy the shit out of Unsounded.

Because if you don’t, I will go Green Mile on you.