Before I go any further, let’s discuss the Current ARC Giveaway Contest. Currently, there are twelve entries for one good reason, two for draw this dog and ZERO for make this face. Basically, anyone with a camera could get this ARC. What the heck, people. You think I’m just going to roll my shoulders and say, “oh well, at least you little dearies tried your best, here have this arc.” NO. This ARC goes NOWHERE until someone makes a Rothfuss face! NOWHERE! AAAAAAAARRRRRRRGH!

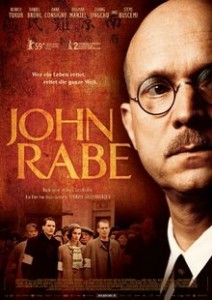

…anyway: John Rabe.

If you don’t know who he is, you really should. And if you haven’t ever read this book, you really should. This is one of the most important stories of World War II, if only because it’s a clear demonstration as to how even the ugliest of horrors can be covered up, forgotten and ignored.

Essentially, the movie follows history fairly faithfully: in 1937, the Japanese Army invades China and conquers the city of Nanking. After the city’s surrender, a six-week massacre follows in which the citizens of Nanking are pillaged, murdered, raped and tortured in a brutal conquest. An international safety zone is established by Nanking’s foreign nationals and headed by John Rabe, a member of the National Socialist Party of Germany. A Nazi. For six weeks, he used his influence and his swastika to influence and protect the citizens of Nanking, housing them in his own back yard when there was no more room in the hospital and girls’ college. Toward the end, as Japanese soldiers jumped the walls with ever-growing daring, Rabe was pulling them off of the girls they were attacking. Eventually, the massacre ends and Rabe returns home to Germany to be arrested by the Gestapo, told never to speak of the incident to anyone and, later, he dies in poverty.

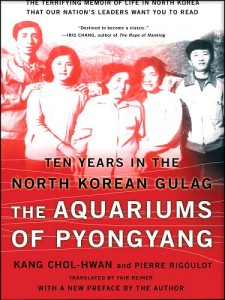

Iris Chang’s book, linked above, comes heavily recommended as a complete account of what happened. The movie remains (mostly) faithful to its history, though there’s a certain Hollywood factor involved that ultimately cheapens it, I think.

To state the positive: this was a film that needed to be made. It’s an incident people need to be aware of, if only because it’s not widely known already. The script is faithful, the acting is wonderfully done and they cover a lot of the more gruesome incidents of the massacre (such as the decapitation contests between Japanese officers) without glamorizing or sensationalizing the gore. Ultimately, it’s an excellent movie that deserves watching and I recommend it wholeheartedly.

I mention this now only because the negative aspects of the movie are going to be the means of discussing an issue I have and, thus, are going to take a little longer to talk about. I want to make this clear so it’s evident I’m not bashing the movie.

I mentioned the Hollywood factor earlier and, given that it’s basically the root of every issue this movie has, it deserves a definition. Basically, the Hollywood factor, as I see it, is the removal of meaning or mood by means of overemphasizing or exaggerating the drama into outspoken or exuberant displays. When a man looks at his dead wife and, instead of just staring blankly, numb with shock, falls to his knees and screams “NOOOOOOO,” that’s the Hollywood factor. When a character of interest is killed via a five-minute-long scene of choking and gurgling as the blood fills his mouth, rather than just giving us the single, fleeting shot of someone we loved disappearing forever, that’s the Hollywood factor.

To be more specific to the film (semi-spoiler alert, though if you know the history, you probably won’t think it much):

At the end, when Rabe leaves Nanking, he is greeted by crowds of grateful Chinese refugees who survived the slaughter, clapping and cheering and chanting his name. They look utterly exuberant. This is roughly the point where I lost my sense in the film.

Perhaps it’s just because I was more intimate with the history, but I felt rather disconnected from the tragedy at this point. This was not just a bad couple of days for Nanking, this was a massacre. Men were lined up for mass executions. Civilians were rounded up and used as sport for killing competitions between ruthless officers. Women were violated in so many ways it’s tasteless to recount them here. When the commanding Japanese officer made it to the site of the carnage, he fell to his knees and wept. Nearly every national involved in the safety zone later committed suicide over what they had witnessed.

This was not the sort of conflict people just walked away from.

I mention this because, as ever, there is something to learn here, even for us fantasy writers.

We talk about fantasy as escapism often and when we think of it, I imagine we think of the ending scene of Return of the King (the first one of twenty, at least), in which everyone stands and dances and celebrates their victory over the hated orcs and the end to the war that claimed thousands of lives. That ending point is what we’re supposed to focus on.

Fantasy can be escapism, sure, but that doesn’t mean it has to be disingenuous. The fact that so many fantasy characters easily recover from their mental wounds is what leads to the cheapening of the conflict. The war seems less like something that was real and more like an unpleasant time that is easily swept under the rug. The hero recovers easily and we’re no longer invested in him, because shit, everything is sunshine and daisies for him at this point.

Keep in mind, this is all fine if what you’re trying to write is exactly that. Many authors have done well with that sort of story. And, as ever, any rule I offer is ultimately trumped by what you, the writer, envision for your story. You don’t need to write a gritty angsty livejournal entry of a story where every fart is a betrayal of trust and every time someone brushes up against the main character’s shoulder it takes years to recover from the mental anguish.

But if you want to establish that mood, that raw grit, that conflict that lingers, then keep in mind that not everyone cheers after a war.

See the movie.

Read the book.

Take a picture of yourself as Patrick Rothfuss.

Peace.

Greenshicts are creatures of legend. Not in the sense that they’re made-up tales to scare children into behavior, but more in the sense that the tales revolving around them are completely true and terrify every sensible adult just as well as they do children. We know a fair amount about the reclusive tribes: they hail from the southern jungles, they are the only tribes of shict to have ever beaten back human incursion and they are exceedingly fond of driving that point home. Usually at the end of a big, heavy stick. For some of the most reclusive and rare shicts in the world, we know a surprising amount about them. But I suppose that’s the entire point of legend, isn’t it?