It’s weird being a child of the internet.

I get annoyed when people bring up memes that I’ve already known about and gotten tired of six weeks before. I’m waiting for the Harlem Shake to catch on in earnest and become even more unbearable. It enrages me to no end that I’m in a position where I can actually say something like: “you still laugh at Grumpy Cat? No, dude, it’s all about Shiba Confessions now.”

That said, though, I’m actually kind of glad that the phrase “grimdark” has caught on enough for us to talk about it.

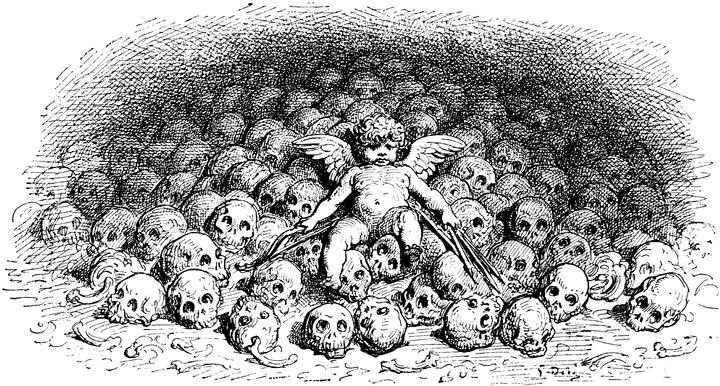

First, a definition: “grimdark” is when a story’s setting, mood or theme is one of relentless violence, despair and grit, usually to a degree that some would find excessive to the point of absurdity. Grimdark tends to be defined as self-serving; that is, grimdark is grimdark for the sake of conveying an exceptionally dark and brutal setting rather than as a product of the story.

It was originally coined to describe the setting of Warhammer 40k, derived from its tagline “in the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war.” And, like all things coined on the internet, it’s undergone quite a few changes in definition and application until it’s pretty much used for whatever someone happens to disagree with or dislike at the time.

Including fantasy novels.

If you run in the same circles I do (and if you’re reading this blog, chances are you do), you’ve probably heard the label applied to authors like Joe Abercrombie, Mark Lawrence, Richard K. Morgan, sometimes George R.R. Martin. All very good authors whose work I have appreciated, despite (and in some cases, because of) their bleakness. And internet labels being what they are, they can’t be considered to have a lot of academic integrity, so nebulous that they can be twisted to apply to just about anything.

Unsurprisingly, and perhaps somewhat justifiably, I think there’s a dismissive attitude toward the word. “Oh, it’s just these people who want to return fantasy to white hats and evil orcs upset that there aren’t enough puppies and rainbows,” they say. “We deal in raw, gritty stuff. The real world.” Grimdark is a word that we’re kind of kicking around with no real discussion going on about it.

And I think that’s a mistake.

As people who make our bread and butter off of words, you’d think we’d know that even the most whimsically-tossed ones have some value. And the fact that we have this particular word to deal with as it pertains to trends in our craft is something that I don’t think we should discount so swiftly.

It’s very easy to sign off accusations of grimdarkness as overreaction, because sometimes it is. There are people who want sunshine, bunnies and rainbows in their books (these people are out of luck). There are people who think it’s morally irresponsible to portray such crass darkness and to not “think of the children” (the people are stupid). But there is a real danger in dismissing the word because there are some questions that should be asked.

How much weight does violence carry?

What’s the worth of a good deed?

Is striving to be a better person an unrealistic goal?

If everything is dark, how can we tell?

How many different ways can we say “people suck, war is hell, the world is a bottomless shithole” and still have it mean something?

And this is where we need to be wary of the meaning behind grimdark. The danger is not in corrupting children or in changing the face of fantasy, but in robbing us, the reader, of the scope of consequence.

Frankly, I think it’s kind of shitty that wanting some hope and love in one’s books is considered unrealistic, on par with rainbows made out of kittens that slide into a pot of gold. It seems like in our quest to be taken seriously as a genre and thus distancing ourselves from a legacy of goodly wizard, naive hobbits and evil orcs, we’ve hit a point where we want to deny everything that made us enjoy these stories in the first place.

Qualities like hope and love, stories about people trying to do the right thing (even if we disagree about what the right thing is sometimes), have a value beyond just making people feel good.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with wanting to explore the darker side of a story. But when we think of the word “explore,” our minds are filled with the ideas of discovery, trekking out into the unknown and seeing what’s on the other side of the hill. We tend to ignore what makes the word so powerful in the first place: where we came from.

Exploration is just as much about where you came from as where you’re going.

Exploration is only impressive because you’re leaving the safe comfort of home behind you. Explorers are only heroes because we know what they’re leaving behind. They have to move from the familiar to the unfamiliar and it’s the familiar that gives the unfamiliar weight and meaning. And it’s the familiar, I think, that’s missing in grimdark.

Grimdark happens when we’re born in shadows. The skies are always dark, people are always terrible, war is ever-present and the heroes are always justified in doing terrible things because that’s just how things are done. We know nothing of the world beyond the fact that it’s shitty. And because it’s shitty, the shit stops stinking. We commit that most heinous of crimes in writing: we become banal.

Violence isn’t shocking, it’s just something to do. Rape isn’t horrifying, it’s a common form of social interaction. War isn’t hell, it’s Monday. Loss isn’t loss because you were going to lose it anyway, so who cares.

It may sound like I’m advocating for an abolition of all violence, horror and grit in fantasy. Anyone who has read literally anything by me can probably tell you that’s a hoark. Truth is, as a reader, I’m kind of advocating for more masochism. I’m asking for you to show me the sunlight so the darkness has more meaning. I’m asking for you to make me love a character so you can hurt him later. I’m asking for you to show me some kindness and hope so that the emptiness where they used to be is all the more profound than if they had never existed at all.

I like it that way, baby.

And the man who does this sort of thing quite excellently is Scott Lynch (who, incidentally, is gearing up to release his third book, hallelujah). His work has a lot of deft wordplay, fast jokes and charming interactions, but no one would dare call it whimsical. And anyone who read The Lies of Locke Lamora can pinpoint exactly the moment where he crushed your soul.

Look, as a dude who has written scenes where the walls are literally painted with blood, I’m aware of the irony of criticism I’m offering here. And honestly, I wonder if I can only really start looking at this carefully given where I’ve come from and what I’ve written. Or maybe it’s just a desire to be different that’s driving me.

My latest work has me asking a lot of these questions. I’m wondering what gives violence its impact: how it happens or who it happens to? I’m wondering what makes a dark world dark: the people who act like shit or the people who don’t? I’m wondering what a dead body means: scenery or conflict?

Maybe you’ll have to tell me if I got it right when it comes out.

Hi Sam,

This does seem to be much in the same vein as some other posts I’ve seen. I haven’t seen someone explicitly defend “Grimdark” as all dark all the time, but that’s the perception this mode gives off.

Even if its bollocks.

That’s kind of the difficulty with arguing things born online. It’s a young word, so it’s not really solid. What one person calls grimdark, another won’t.

yay, Paul said bollocks

As with many concepts, grimdark needs to be defined as much by what is is NOT as by what it IS. It’s no use to debate a concept that people tend to ascribe to anything that doesn’t fit their own personal peccadillos – look no further than the current discussion over cyberbullying to demonstrate my point. With that in mind, in my view, it does positive harm to the discussion to use such a wide net as to catch writers such as Joe Abercrombie under the definition (assuming you’re referring to his The First Law books). If his trilogy is grimdark, then so is Tolkien’s. And, as to George RR Martin’s books, they are certainly brutal, but grimdark? You feel every stab and stitch in ASOIAF!

Now, I remember reading The King’s Dragon a few years back, Kate Elliot’s book, and it struck me as extremely brutal…I wonder if that was just my age/literary maturity at the time. Maybe I’d feel the same sense of hope that I found at the end of A Dance with Dragons.

Personally, I disagree with the assessment of Abercrombie as “grimdark,” though I’m going more off BEST SERVED COLD. The meat of that story came in Shivers’ failure to be a good person (which is the sort of thing I’m arguing for). Martin’s books are extremely effective through this concept, as well. It could be that I’m just applying my own experience across the board, but I think a lot of readers come to Martin’s books expecting it to follow some genre tropes and it succeeds with great measure by defying those.

I mean, who didn’t fervently keep on reading after Ned Stark’s…incident to make sure he was okay?

So, you’re right. Perception plays a huge part of it and it’s difficult to argue perception. But at the same time, it’s undeniable that Martin changed the game and the tone got pretty grim after ASOIAF came out. And as the game got changed, I think a lot of people wanted to try what Martin was doing and, in doing so, probably overshot it.

I’ve not really been following the grimdark debate that seems to have appeared in recent days, it seems to have coincided with Joe Abercrombie’s debut on twitter (@Lordgrimdark), perhaps that is what sparked it off. I’m not sure I really understand what the issue is. Is it about the balance between light and shade? Are we saying that detractors of Grimdark (or Fantasy Noir as I thought it was known) are ignorant of its strengths or that some authors (nobody seems to be actually naming any that have this quality) have taken the darkness too far by obliterating all light in their work?

Admittedly, Joe’s debut to twitter did inspire this a little, though more because he’s one of the most self-aware writers I’ve ever seen, hence I figured this must be big enough for several authors to have noticed.

I don’t think we’re quite at the point where we’re starting to argue the specifics of grimdark, really. Right now, I think we’re just figuring out what it is, whether it’s worth paying attention to and where we fit within it.

Pingback: Stopping the Pendulum « Bloodlust: Domains of the Chosen

Pingback: Gritty, Grimdark, and Gratuitous « Bloodlust: Domains of the Chosen

Pingback: It’s still very grimdark out there | Cora Buhlert

Pingback: Linkspam on Fantasy, Realism, and “Grit” | Jenny's Library