First things first!

I’m going to call the deadline for this here giveaway in which you can net yourself a couple of fine, signed copies of Tome of the Undergates and Black Halo by the end of this week. So if you’re figuring on fixin’ to take one, you might as well send me a post!

Also, if you’ve been wanting to hear my melodic voice as I gush quietly about Batman and Gail Carriger, why not have a look at this podcast I did for Touching for the Monolith. I guarantee no monoliths were touched without express consent. If that’s still not enough for you, you might want to check out this interview I did over at Drying Ink Books.

Okay.

Let me tell you about Moneyball.

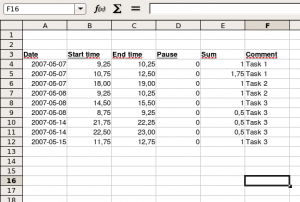

Here, look at this image:

Now look at this one:

Now look at this one:

Congratulations. You have now seen Moneyball.

Brad Pitt stares off into the distance. Jonah Hill does something slightly awkward. Then there is math.

It is boring. If you see it, you are a bad person. Like me. You spit on children and put orphaned kittens into families that cannot and will not ever understand them. You think math is fun and when you die and reach whatever dark hole your soul is going to, you will have slushies poured down your pants and get a lot of wedgie’s from Satan’s jocks.

Admittedly, I am not a tremendous sports guy. My repertoire of buzzwords that I bust out whenever the conversation switches to sport is limited to “penetrating offense,” “tight end,” “rear play,” “Bangkok rules,” “dirigible maneuver” and “groin-slappingly good.” I do like hockey, owing to the corrupting influence of nefarious Canadians, but that’s about it. I find soccer boring, football weird, rugby unexciting unless I’m watching the All Blacks, baseball brings up tragic memories and I absolutely cannot abide volleyball and have burned many nets out of protest.

You could say Moneyball was not meant for me.

But I’m having a hard time figuring out who Moneyball is for. I get that it’s all about how the sport of baseball was revolutionized by way of math from a sport in which chubby men in pajamas grunted and spat and talked about “feelin’ the grip of a ball as it clocks you square in the beanbag” to a sport in which people obsessively discuss stats and percentages with all the fervor of World of Warcraft raiders. In truth, this movie is a quiet tribute to a victory by nerds. But those nerds are math nerds, mortal enemy of the arts nerds, the kinds of nerds who use phrases like “warp drive” and “hyperion engines” and “don’t hit me with that stick.”

But the reality of the movie is that it’s pretty boring. It’s a glorified documentary featuring more believable dramatizations. It’s a lot of discussion about statistics and doing things your own way with a very hamhanded helping of emotional manipulation shoveled down your craw in the most predictable of ways.

In truth, I might be baggin’ on Moneyball simply because it’s a mirror held up to my face and I’m seeing a very hideous reflection. Halfway through the movie, when I saw Brad Pitt’s character meeting his daughter by his divorced wife, I realized I was being emotionally manipulated. Chiefly because once a kid is introduced, she either dies or someone else dies for her and it’s a very cheap way to introduce emotional tension without actually having to develop a character.

And in truth, I don’t actually mind that a movie tries to emotionally manipulate me. Nor do I entirely mind when I realize it is. What I mind is when I get no emotional payoff to go with that manipulation. If a dude makes a grand, eloquent speech, there better be a big, badass battle to go along with it. If a cop says he’s two days from retirement, he better get shot in the next scene. If two lovers tenderly look into each others’ eyes and confess the feelings they’ve always been afraid of, one of them better get kidnapped, tortured and have his/her mutilated body show up on the other’s doorstep.

And this is where Moneyball sheds an uncomfortable truth on me. I’m an elitist. A reverse elitist. I like big, cheesy payoffs. I like sappy stories. I’m not as patient as I thought I was and I have a hard time accepting emotional manipulation that doesn’t have an emotional outcome.

And yet, I’m okay with that. As okay as I am saying that Moneyball is boring. It’s boring and dull and predictable and someone thought it needed a humanistic angle that went nowhere and I’m totally okay with saying that I want it to go get hit by a truck.

If you see it, I’ll beat you up and take your lunch money.

Since I have seen the movie AND read the book, I guess that means you get my lunch money for the next week.

The movie was boring; the book was very good. The problem is most people, including the morons who made the movie, missed the point of the book — which simply is that if you are at a competitive disadvantage because of financial disparities, you need to look for assets that are undervalued if you want to compete with the big boys. This can apply to business, sports, family reunions, whatever.

In Moneyball, the Athletics could not financially able to compete with the Yankees and other high budget teams. To cover the talent gap, Beane (Pitt) looked for players who were really good at one skill that helped a team win (getting on base) but who had poor skills in other areas (defense, for example) that made them affordable to the Athletics and disposable to other teams. Using that, the Athletics were able to field winning teams for most of the 2000s. The league eventually caught up to them and the ability to get on base is no longer a cheap, undervalued skill. In short Moneyball is about exploiting market inefficiencies to your advantage.

How the hell they made a movie out of that still boggles my mind. But, in Moneyball’s defense, boring as it was, it did not descend to “English Patient” level boring. Small blessings should not be ignored.

I had never read the book, sadly. I should have prefaced that I totally appreciate the message of this movie and I get the importance of it all, but it’s one of those concepts that works great as a lecture, an amazing fact or anything that is not a film.

It’s also true that I was unfair and didn’t represent accurately in my insane babbling the parts of Moneyball I really liked: the railing against the establishment, the defiance of the old boys’ club, the hardship and bloodshed that comes from going your own way.

You’re dead on about the big publishers, of course. And in fact, there comes a point where it’s less about the quality and more about the communal perception. Tell someone every day at the same time that the sky is orange for sixty years, he’ll probably end up believing it in some small way. Shove enough Patterson in enough peoples’ faces and you’ll eventually get people who pay attention to him.

But I didn’t at all like the daughter aspect. To me, it felt shoehorned in as a way to play a human angle on an interesting (but not gripping) facet of baseball lore. And in fact, I’m not quite sure how this could be improved. The subject seems more fitted for a documentary, not a feature film. It lacks humanity, it lacks passion. It’s romantic in the same way that sunsets on the beach are romantic: because people say they are.

Semi-ironic, anyway. Thank you for the opinion, though.

well if you don’t have the daughter, how do you explain why he didn’t take the money and go to Boston?

I don’t know. I would have liked to think it would have been him deciding to stick to his scruples and say that the money didn’t, in fact, matter as much as everyone thought it did.